While they were courting, Gus would take the streetcar across town to her home at 4116 Whitman Ave., near the old Lourdes Academy. Many times after their dates, Gus, who rose before dawn to work in the bakery, would fall asleep on the streetcar on the way home and ended up riding it back out to the West Side.

Their marriage produced five children – Leona, Ruth, Kathleen (Curly), Eileen and Jim -- and a host of grandchildren and great-grandchildren, and this is part of their story. It is a story of a family and a family business.

Gus Hausser’s roots

August “Gus” Hausser was born in Cleveland in 1891, first child of German immigrants Anna Gilles and August Hausser.

Anna Gilles, grandmother to the Hungry Five, said that her family left Germany so her brothers would not have to serve in the Kaiser’s army. In the 1880s, when the Gilleses left, the Germany of the northeast was Prussian, Protestant, and militaristic. This ideology and political philosophy clashed with that of the German Catholics in the south and west of Germany. They lived in the west, in a village called Landkern, not far from Coblenz and the Rhine River. So it was natural that Anna’s father, Anton, and mother, Maria Elizabeth (Berenz), would decide that things might be better elsewhere. At the time, 90,000 Germans a year were immigrating to the United States.

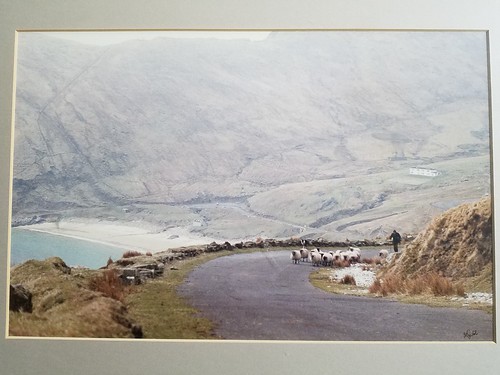

|

| The Gilleses came from a village near Coblenz. |

The first to cross the water was Anna’s brother Nicklaus, who had come with family friends in 1881. He worked out west in Nebraska, among other places. His short self-published autobiography is here. About six years later, the head of the family, Anton, came to Cleveland to establish himself and earn enough money to bring over the rest of his family. The first to join him was the eldest son, Johann, 20. A passenger list in the Library of Congress shows that Johann Gilles came over by himself on the ship Rhynland, from Antwerp, Belgium. He arrived in New York on Aug. 31, 1888. The ship’s manifest lists his destination as Cleveland. On April 15, 1889, the remaining 10 Gilleses (mother and nine children; the 12th child was born in America) arrived in New York from Rotterdam aboard the ship Amsterdam. Anna, 17, was the oldest of the Gilles children aboard that ship.

A sad side note. Gilles-Sweet elementary school is named for two Fairview Park men who served in the military and died during World War I, one of them being Fred Gilles, son of Nick, the first Gilles who immigrated to the U.S. Fred became ill and died during the flu epidemic in 1918 while at Camp Zachary Taylor, the Army's largest training base, near Louisville, Ky.

Anna later told her children and grandchildren how she had worked as a housekeeper in a castle on the Rhine. When she first arrived in this country, Anna did the same kind of work for a Jewish family on the East Side. The Gilles family eventually settled in a house at 1616 E. 36th St., then known as Aaron St. (Anna's daughter, Elsie Hausser, described it in her own family history, from which I am borrowing heavily. This history is rich in detail.)

German at home

Anna’s grandchildren recall that she would sometimes converse in German with her son, Gus, to keep the children from knowing what they were talking about. But at times, she resisted speaking German. Grandson Jim recalls a scene in the bakery between Anna and Gus in which he was speaking German to her, but she insisted on replying to her son in English.

Ruth recalls running errands for her grandmother. “I did her grocery shopping after school from fourth grade on and made 25 cents a week. Can’t remember how often – not every day but more than weekly. People shopped more often then because they didn’t have freezers and refrigerators, only iceboxes with real ice, so food didn’t keep as long then. She was always very kind. All the customers of the bakery liked her very much. She took the time to chat with them. She said they were her livelihood, which was true, but it was more than that. She was truly interested in them. She had varicose veins and wore heavy elastic stockings but never complained. As time went on, she spent less time in the store, because of her health, I suppose. And we, the granddaughters, began taking our turns working after school in the bakery in high school and full time as the business grew.”

The Gilles Family reunions. As children growing up in the 1950s, we Breiners would go to an annual picnic called the Gilles reunion, which for us meant ice cream, hot dogs, and participating in all kinds of games and competitive events. We really did not understand the family connection: Anna Gilles was our great-grandmother, and she had died in 1940, a person as distant in a child's mind as, perhaps, George Washington. Anna and her 11 brothers and sisters had big families, so my grandfather, Gus Hausser, had 54 first cousins, and who knows how many our mother had. We were in the next generation. I don't remember attending those events much after I turned about 10, in 1961. Either we stopped attending or the reunions stopped being a good idea. In the early 2000s I contacted a Gilles relative in Anaheim, Calif., who had a database of more than 300 descendants on a CD-ROM. Martha (Sabol) Wright has provided this photo from the 1954 reunion, which includes Breiners, Hearns, and Haussers (marked with red dots). Let me know if I missed marking anyone in the photo.

The Gilles Family reunions. As children growing up in the 1950s, we Breiners would go to an annual picnic called the Gilles reunion, which for us meant ice cream, hot dogs, and participating in all kinds of games and competitive events. We really did not understand the family connection: Anna Gilles was our great-grandmother, and she had died in 1940, a person as distant in a child's mind as, perhaps, George Washington. Anna and her 11 brothers and sisters had big families, so my grandfather, Gus Hausser, had 54 first cousins, and who knows how many our mother had. We were in the next generation. I don't remember attending those events much after I turned about 10, in 1961. Either we stopped attending or the reunions stopped being a good idea. In the early 2000s I contacted a Gilles relative in Anaheim, Calif., who had a database of more than 300 descendants on a CD-ROM. Martha (Sabol) Wright has provided this photo from the 1954 reunion, which includes Breiners, Hearns, and Haussers (marked with red dots). Let me know if I missed marking anyone in the photo. The first of three bakers

Anna’s future husband, August Hausser, immigrated to this country from Germany at age 21, around 1888. His mother had died of smallpox when he was young. His stepmother was cruel and unkind to the children, who one by one left home and came to America. August had learned the baking trade in Germany, so he had a skill to work with when he arrived here. His son and grandson would follow him in the craft.

His daughter, Elsie Hausser, said in 1981 that August was from Wittenberg, made famous by Martin Luther, in northeast Germany. This would make sense, since August was a Lutheran. But family members reported in the 1920 census that his birthplace was Stuttgart, which is in the western province of Wurttemberg. Maybe both are true; he was born in one place and grew up in another. Or this could be one time that Elsie, a very detail-oriented and precise person, was mistaken. If so, she could be forgiven. Wittenberg and Wurttemberg sound similar in German.

It is not known how August and Anna met. They were married in 1890, when Anna was 19, a year after she arrived in this country. August and Anna had four children, August (Gus), Elsie, George and Herbert. In 1902, August Hausser rented a bakery at 3811 Payne Ave. on the East Side, and the family lived in the attached home. The bakery was in the back, the living quarters in the middle and the shop in the front, so the bakers had to walk through the living room with the baked goods destined for the store. Elsie recalls that they would track flour through the house. It annoyed her because it was her job to clean up after them.

Sneaky Catholics

One of the biggest issues in the family was religion. August was a Lutheran. Before their marriage, he promised Anna Gilles that their children could be raised Catholic. But he didn’t keep his promise. So Anna would sneak out of the house to go to church, probably at St. Peter’s on E. 17th St. (The church is in fine condition at this writing in 2003). She also contrived to have her sister, Gertrude, who was living with them, sneak the two youngest boys out of the house and have them baptized. None of the children were raised as Catholics until after their father’s death. Then they all entered the church and took instruction. The elder Hausser might have been horrified to learn that one of his sons, George, went so far as to spend some years studying to be a Catholic priest.

August Hausser died of tuberculosis in 1909, at age 42, leaving his wife, 38, to take care of four children on her own. Fortunately, he had saved $6,000 in cash and had a $1,500 life insurance policy. His oldest son, Gus, 17, had been working in the bakery for several years, so he was not totally unprepared for his new role. He was to be the second Hausser baker. As Gus’s younger sister, Elsie Hausser, recounted in her 1981 family history, the bakery was in a crisis at that time. It had lost its biggest customer, who was skittish about buying from a store whose proprietor had died of a deadly infectious disease.

However, Anna found other customers, survived and prospered. She was fortunate to be surrounded by siblings and their spouses, who offered help and advice. In 1913 Anna had the opportunity to buy a bakery and 10-room house at E. 85th and Superior, and paid $10,000 cash for it. The family moved upstairs -- Anna, her sister Gertrude and the four children.

(A side note: After August Hausser’s death, his brother, Fred, and his wife, Louise, who lived in Hartford, Conn., kept in touch. One year at Christmas, they sent August’s granddaughters a dollhouse. “Oh, it was a beauty, it was beautiful,” Leona recalls. “We gave it later on to Uncle Herb’s two daughters, Marilyn and Janet. [Herb Hausser, brother of Leona’s father, Gus]. It was wonderful, a beautiful thing. They mailed it. Can you imagine that?” Fred Hausser’s son Milton later became an insurance agent and was living in West Hartford, Conn., in 1973 when Jim Breiner visited him. At the time he was breathing from an oxygen tank because of emphysema, brought on by smoking three packs of cigarettes a day. Milton had one son, Lee, who was living in that area.)

Anna continued to run the bakery with Gus and Elsie helping. “She was a beautiful woman, really,” granddaughter Leona says of Anna. “Beautiful long blond hair all twisted up in the back. My uncles and my father were really very protective of her in so many ways. They didn’t want her on her feet all the time. And if they were going out somewhere at night, I would go over there and sleep with her overnight. I remember she braided her hair and she taught me to braid it. And I said, when I get big, I can get long hair and braid it like you. [Leona laughs at this; she became a nun and had to wear her hair short]. Very sweet. She really stood up to my Aunt Elsie. My Aunt Elsie said she was sure that the bums, as they were called, came from the park and came to us first because they knew they could get a handout. Elsie said, ‘They’ve got us spotted, Mom.’ And grandmother said, ‘Never mind, never mind,’ and gave them what they needed.”

Education first

The three of them -- Anna, son Gus and daughter Elsie -- ran the business. Gus managed production and Elsie eventually ran the shop out front. That bakery provided the means to send the younger boys, George and Herb, to good schools. George went to Loyola College (now St. Ignatius High School), and Herb attended a business school downtown. The bakery’s earnings also paid for all five of Gus’s children to attend Catholic high schools, the girls at Notre Dame Academy and Jim at St. Ignatius. It was only years later that they learned their grandmother had paid their tuition because their father’s salary would not cover it. Later George and Elsie made sure that Gus’s grandchildren could attend Catholic high schools as well.

Elsie’s generosity was matched by her high expectations. “She was a tough lady to work for,” Leona recalls. “We were readers, so we all had a turn at the bakery, and we would bring a book over for when nothing was going on, and, absolutely, no reading, you had to be busy. Look busy even if you weren’t, that was her expression. Later on we found out, long after, that she had dated one fellow and they were very serious and he just dumped her without a word and she never got over it. She never dated. She worked hard all her life.”

Ruth writes, “Uncle George and Aunt Elsie [brother and sister] were my godparents. Well, how lucky can you get. Elsie insisted on paying for my wedding gown. She and her girlfriend, Helen Keller, also a maiden lady, went with me to Faster Frocks, a special shop on Carnegie for wedding stuff. Looking back, I think they enjoyed the whole process, and it’s really very touching – these two ladies who never had the chance to wear one themselves going through the process of selecting a wedding gown.”

|

| Herb Hausser in 1988. He had a great mind for business. At left, his niece, Eileen (Hausser) Hearn |

George was the intellectual of the family and had a dry wit. He was drawn toward theology and philosophy. Ruth recalls that her Uncle George spent some years in seminary. He was supposed to go to Rome and study, but he left because there was not enough intellectual inquiry to suit him. Still, he went back, tried again and then decided it was not for him. He had a last interview with Bishop Schrembs, who was “very kind.” Ruth says, “Someone, I don’t remember who, told me that he repaid the diocese for the money spent on his education after he had a job. Bishop Schrembs commented that he was the first person to ever do that.”

|

| George Hausser in Army uniform with niece, Ruth, and her fiancee, Dick Breiner. George was 39 when he was drafted to serve in World War II. Dick was in training in the Army Air Corps. |

Gus Hausser

|

| Gus and daughter, probably Leona. Around 1920. |

He met Anna Frances “Nan” Lavelle at a dance on the west side. When he called Nan to ask her for a date, she hesitated because he wasn’t such a good dancer. “She was as Irish as can be on her side, and he was as German as can be on ours,” Leona recalls of her parents. “My father’s family said, Why couldn’t you find a nice German girl? But my father just laughed and didn’t give them any answer.”

They were married in 1916. Gus liked to call his wife “Mike,” and she seemed to like the name too. Nan would not discuss her age, even with her children. To this day, her children are still uncertain of her age and how much older she was than her husband. It was five years.

The Hausser children recall their father, Gus, as a gentle, creative man. “He was a sweetheart,” Curly says. “He was just a perfect person,” Jim says. He liked to draw. He liked to read. He was reserved but had a good sense of humor.

He was better at dealing with the kids than his wife. “Whenever things would get bad at home and my mother couldn’t handle us anymore, she would say, go over and tell your father what you’re doing. So we had to go over to the shop and tell him, and his punishment always was you sat in one corner on a turned-over lard can, and the other one sat in the other corner and you just sat there. And then the salesman would come in and say, Who are these kids, and then my father would say, 'Imagine, two kids, same family, they can’t get along, and their mother doesn’t know what to do with them.' My mother had trouble dealing with us. They were total opposites really.”

A family of readers

Ruth recalls that her father would read to her. “The first book I ever heard read to me (and Leona), sitting on my father’s lap in the big leather rocking chair, was ‘Heidi.’ I loved it. He would read one chapter at a time. Next was ‘Pinocchio.’ Later I liked to read biography. Amelia Earhart was one. And still later I liked detective stories. Philo Vance, I think, was one author. Sherlock Holmes, of course.”

Gus and Nan made their home upstairs in the bakery building. They lived on the other side from Gus’s mother, aunt and young siblings. It was after they had their first two children, Leona, born in 1917, and Ruth, born in 1920, that they realized they needed a place of their own.

The children heard a lot of German spoken by their grandmother and aunt. Gus’s Irish bride was worried that her children might grow up speaking German. When Leona, a toddler, ran her finger across a dirty window and said “Dreck,” German for dirt, that was the last straw.

They moved around the corner to a double house at 1250 E. 84th St. Another family, the Wolfes, rented the upstairs. It was convenient for Gus, the baker, who just walked around the corner to the shop. Eventually, the family grew to five children, and the seven Haussers made do with two bedrooms. The front bedroom was for the parents. The small bedroom in the back with two single beds was for the four girls. There was first a crib and then a couch that Jim slept on. When Leona was a freshman in high school, they asked the tenants to leave and took over the upstairs as well.

Anna Frances “Nan” Lavelle

As calm and reserved as Gus Hausser was, his wife, Nan, was the opposite. She came from a large, talkative Irish family. Her children recall that when she would get together with her brothers and sisters, they would get emotional and carry on at high volume and all at once. To some outsiders, their normal conversation sounded like quarreling.

Anna Frances “Nan” Lavelle could trace her roots back to Achill Island in County Mayo in the west of Ireland. Her father, John Patrick Lavelle, had come to this country in 1875 when he was 17 years old, part of a wave of immigrants from that impoverished agricultural area. Many of them, like young John, found a kind of work that illiterate men were qualified for -- they unloaded coal, iron ore, lumber and grain from the Great Lakes ships that docked on the Cuyahoga River.

Most of the Irish laborers lived nearby in what was known as the Angle, and they attended St. Malachi’s Church. The more well-to-do Irish, known as the lace curtain crowd, looked down on the laborers, who were referred to as shanty Irish or pig-in-the-parlor Irish. An especially insulting term was “Achill Irish,” wrote William F. Hickey, in “Irish Americans and Their Communities of Cleveland” (Cleveland State University, 1978). It alluded to “the supposed traitorous conduct of the people who inhabited that island” during the famine times. But Hickey does not explain what that betrayal might have been.

|

| Achill lies off the northwest coast but is linked to the mainland by a bridge. |

The “Topographical Dictionary of Ireland” of 1837 gave the population of Achill as 5,277, which is about 1,000 more than what it is today in 2003. The island is about 16 miles long and 7 miles wide. In the 19th century it was principally owned by one man, Baronet Sir Richard O’Donnell. At that time there was no church on the island, being a poor community, but every Sunday a mass was performed in English and then in Irish at Dugarth. There were no proper schools. This explains why many Irish who immigrated were illiterate.

The man who would be Nan's father, John Patrick Lavelle, the Achill immigrant, landed in the same neighborhood in Cleveland as Bridget Ellen Gallagher. She was born in Cleveland in 1862 to Martin Joseph Gallagher and Ellen (nee Joyce) who also had emigrated from Achill two years before John. There was work available on the docks for Martin Gallagher as well. Bridget, the Gallaghers’ oldest daughter, became a serving girl. Her family was living at 34 State St. (what was later called W. 29th St.) when Bridget, 18, married John Patrick Lavelle, 22, at St. Malachi’s Church on Nov. 23, 1880.

The neighborhood was a thriving Irish community. A look at census records from 1870 and 1880 shows large Irish families living in close quarters of this West Side ward. John and Bridget Lavelle set up housekeeping in the same neighborhood, on a street called Bentley Alley, which was later taken to make way for the Shoreway. Eventually, they had 10 children. Their fourth was Anna Frances “Nan.”

Although the Lavelle name looks French, it is very Irish. Lavelle is the anglicized form of the Irish Ó Maolfábhail. In some places it takes the form of Mulfaal, Mulvihil or Melville. Lavelle is the usual form: it often occurs in County Mayo, where Lawell is a variant of Lavelle.

When Bridget Lavelle was pregnant with her 10th child, in 1901, her husband died at age 42. It must have been a difficult time for the family. The oldest daughter was 19, and Nan was 14. She never went past the sixth grade. Likely Nan did not marry for another 16 years because she was helping support the younger children.

|

| 4116 Whitman Ave., near Bridge Avenue and W. 41st St. Lavelle home at the time of the 1910 census. |

In 1910, when Nan was 24, the family was living at 4116 Whitman Ave. on the West Side, just north of Bridge Avenue near the old Lourdes Academy. According to that year's census, Nan was working as a telephone operator, and her sisters were working as well -- one as a clerk at an auto company, one as a stenographer and another as a telephone operator. It could just be a mistake of the census taker, or it could be another example of Nan's sensitivity about her age and marital status, but the 1910 census shows her age as 21 when she was actually 24. Did she lie to the census taker?

Nan was the only one of the Lavelle sisters whose spouse wasn’t also Irish. Because Nan was living on the East Side and her family were West Siders, most of the Hausser kids did not know the Lavelles that well. Leona often spent summers with the West Side relations, but her younger sister, Ruth, says that they saw the Lavelles at Christmas and not much more often than that.

Ruth, however, did spend an extended period with Nan’s sister Kitty. Ruth was about 15 months old when her mother gave birth to twins, Eileen and Kathleen (Curly). Nan asked Kitty and her husband, Ed Murphy, to take care of Ruth for a time because she had her hands full. Kitty and Ed had no children. Neither Leona nor Ruth is sure how long this arrangement continued, but it was probably more than a year.

Kitty wanted to adopt Ruth. “Kitty thought my mother was very selfish because she already had three girls,” Leona says. And when Kitty brought Ruth back to her mother, there was a scene. Leona, who would have been about 6, says Ruth did not want to stay with the Haussers but wanted to go “home” with Kitty. “You ARE home,” Nan said to her daughter. And when Kitty protested, Nan said, “SHE’S MY DAUGHTER.” And that was that.

|

| The Lavelle family home in 1920, 1283 W. 111th St. They moved here after Nan was married. |

Maybe this contributed to Ruth’s difficulties with her mother. “Ruth was a smart girl and she had questions, and my mother considered that ‘answering back,’ which the expression was in those days,” Leona says. “[Mother] was just a tough woman, that’s all. She was hard on us. She had rules, and if you didn’t observe them you got a wallop. We all agreed that she did her best. She sewed each of us a lot of our clothes. She made our uniforms, and they fit because she measured them, whereas the other kids at Notre Dame Academy had baggy uniforms.” She could borrow a dress or skirt, look it over and quickly duplicate it without using a pattern. “I think they all [the Lavelle girls] learned how to sew.”

By the time the younger Hausser kids knew Nan’s mother, Bridget (Gallagher) Lavelle, she was very hard of hearing and kept to a chair. They do not remember much else about her. Nan took care of her at the end of her life, when she was completely bedridden. Bridget died in 1942.

Summers at the beach

The family used to take a cottage occasionally at Stop 62, Lake Road, in Avon Lake, an allotment where many bakers owned cottages. “The drive from East 84th Street seemed to take forever,” Ruth says. “There was a bucket in the back seat beside the five kids for whichever one would throw up. I’ve often wondered since how our parents could stand the trip. It’s funny, but nobody got car sick on the way home. Just the trip out. We sang songs on the way home:

Now the sun is sinking

In the golden west

Birds and bees and children

All have gone to rest.

|

| In the driveway of the house on E. 84th St. Jim Hausser is in front, twins Eileen and Kathleen are behind him and then Ruth, mother Nan, Leona, and, at right, their upstairs neighbor, Mrs. Wolfe. |

“In 1929 St. Thomas Aquinas school was built and the dedication took place in November of that year,” Ruth writes. “The bishop was scheduled to come and bless the building at Thanksgiving. The day before, I was called to the principal’s office and told that I was to present him with a basket of flowers, was given a speech to memorize and was asked, ‘did I have a white dress to wear.’ My mother found one someplace. I worked on memorizing the short speech, and next day nervously went off to do my thing. In the priest house, waiting for the bishop to come down from the second floor, I began to panic. I went completely blank and forgot the whole thing. I’m sure I cried. Somebody produced a copy of the speech, and I read it as my hands shook mightily and the Bishop patted me on the head. To this day I can recite that little speech from memory. But not that day. I was nine years old.”

The kids in the neighborhood seemed to like playing in the Haussers’ yard. Jim recalls that a neighbor boy with very strict parents, Jim Kacirk, came over to play one day in his meticulously kept outfit. “His parents wouldn’t let him walk across the grass except to cut it.” But the Hausser kids had him playing in the dirt in no time. Seventy years later, Jim has stayed in touch with his neighborhood friend, who still says that playing with the Haussers was his “salvation” from a strict home environment.

Eileen remembers that some of the other kids in the neighborhood thought the Haussers were rich because their family had a business of their own. To her, that was a laugh. If they were rich, why would their mother take the trouble to bleach old flour sacks and make them into bloomers for the girls? Sometimes the bleach wouldn’t remove all of the ink. So Eileen’s retort to the “rich kid” remark was, “If you think I’m a rich kid, then I’m the only one who has General Mills on the back of her bloomers.”

Leona wanted to enter the convent after finishing at Notre Dame

Academy, but took the advice of a priest to work for a year. She got a

job at Higbee’s Silver Grill Tea Room and worked there before entering

the convent at 18. She stayed in the Notre Dame order from 1936 until

1970, when the extremely rigid, uncharitable environment became more

than she could bear. She left to join the sisters of the Holy Humility of Mary, also known as the Blue Nuns. Leona taught high school and college English for many years.

Eileen enjoyed roller-skating to the library on E. 79th St. and,

later, when they were bigger, to the library on E. 105th. She had a gift

for drawing and was the one who produced the best cake decorations of

the bunch. “I did enjoy that,” Eileen says. “She was a wonderful

artist,” Curly says. Eileen remembers walking to the art museum for a

drawing class and doing a study of a suit of armor. She downplays her

artistic skills. “I was a good copier.” But all of her siblings

disagree. She had real artistic talent, they say.

Eileen and Dick Hearn

Eileen was a sophomore in

high school, roller skating at Euclid Beach Park, when she met a

football player from Cathedral Latin named Dick Hearn. Eleven years

later they were married. Dick had served with the Marines who were protecting the Panama Canal during WWII.

|

| Ruth, Kathleen (Curly), and Eileen Hausser |

Ruth, Eileen and Curly

The kids did not see much of their Dad, even though he was working just around the corner. He would rise every day before dawn to start making the baked goods and would not return home many days until 12 or 14 hours later. Later, all of the girls and Jim put in time working in the bakery or behind the counter. Elsie ran the store in her strict, regimented fashion. Curly worked there for eight years, from 1944, when Ruth got married, to 1952.

One day Curly had it out with Elsie and walked out of the store. The next week, though, she and Elsie had a talk and made amends, and Elsie began treating her better. It must have been the pressure of running the business that made her so strict, Curly says. Because after the bakery business was sold in 1957, Elsie became a different person -- much more relaxed and easy to get along with. She became the gracious hostess at the house she and George shared on Carver Road in Cleveland Heights.

Curly and Andy

It was in the bakery that Curly noticed a young man who seemed to treat his wife with impressive kindness. Curly thought she would like to be treated like that. As it turned out, the young man was not married. Andy Sabol’s companion was his sister, not his wife, and Curly got to know this gentle man, who was a WWII combat veteran. She and Andy married in 1952.

He won a Battlefield Commendation for "going behind enemy lines to string radio wire while under fire," but the remaining details of what he was awarded were lost in the fire at the National Personnel Records Center in 1973. He had great respect and admiration for Gen. Patton.

After the war, Andy went to work at radio station WERE 1300 in Cleveland.

"They were a perfect match," their daughter. Martha, recalled. "They cherished each other!"

Jim and Lois

Jim recalls that the neighborhood around E. 84th Street was filled with relatives from the Gilles side of the family -- the Roeders, the Soeders and a second cousin, Larry Gilles. When he was older, Jim and cousin Larry went to a dance at a place next door to the old Cleveland Arena on Euclid Avenue and met the Mathews sisters, Lois and Alice. Jim and Lois eventually married.

|

| Andy Sabol, right, at the Hausser family reunion in 1988. At left, Ruth (Hausser) Breiner. |

Despite the fact that all three other sisters vowed they would never work in the bakery again after high school, and all went to work elsewhere, all of them eventually returned to help. Ruth and her younger sisters, Curly and Eileen, worked in the bakery until they were married. Ruth and Dick Breiner, whom she met at the home of a Notre Dame classmate, were married in 1944 while he was in the Army Air Corps. Their first child, Richard, born in 1945, was the first child of the third generation of Haussers.

Gus Hausser did get to see his first grandchild but did not live much longer. He contracted colon cancer and died in 1946. That left his sister, Elsie, in charge of the store.

The third baker

Gus’s son, Jim, was just coming back from the war at this time. He had entered the Marines less than a year after graduating from St. Ignatius in 1942 and was an airplane mechanic in the Philippine Islands. He worked on the naval version of the B-25 bomber, called the PBJ. Like his sisters, he did not want to work in the family bakery. But Elsie, who was not skilled at dealing with people, was having trouble with the bakers and asked Jim to come back. His first day was a hot one. He remembers walking into the baking area and being hit with the sickly, sweet smell of yeast and rising dough. He thought to himself that he would never get used to this.

He ended up running the bakery with Elsie for the next 11 years. They sold the business in 1957 to a man named Gordon, who did not manage to keep the operation running for very long. The Hausser family had been in the bakery business for 55 years. Jim worked another 30 years as a baker for Hough Bakery. He was the third and last of this line of Hausser bakers.

|

| Eileen (Hausser) Hearn and husband, Dick, right rear, with their five children, spouses, and grandkids. Mentor, 1981. |

German-Irish tension

Elsie Hausser never approved of what she considered the Lavelles’ extravagance in buying their house on W. 111th St. Her clear-headed business sense proved on target when the Lavelle household, then supported mainly or exclusively by Florence, suffered a Depression-era catastrophe. They lost the house. Nelson J. Callahan and William F. Hickey, writing in “Irish Americans and Their Communities of Cleveland” (Cleveland State University, 1978) wrote that the Germans considered the Irish “improvident wastrels.” Hickey says, “….all through the latter decades of the 19th century, the Irish of Cleveland were blamed for every major and minor ill that afflicted the city.” The anti-Irish Cleveland Leader reported that 90 percent of all violent crimes committed in Cleveland from 1850 to 1870 were committed by Irish.

The vast majority of Cleveland’s Irish came from County Mayo, Callahan says. “Few counties were and are as poor as County Mayo.” Perhaps some of the Mayo people are our cousins. Among the common Achill names are Gallagher, Kilbane, Lavelle, O’Connor, O’Malley, Joyce, and Patton. Two Mayo men named Gallagher made their mark in Cleveland, but it is not known if they are relations of ours. In the 1850s, Anthony Aaron Gallagher, who spent his first years in Cleveland unloading iron ore, approached ship owners and, for a commission, took full responsibility for the hiring and firing of the Irish stevedores. Another, known only as Holy Water Gallagher, arrived in Cleveland from Mayo in 1847, and he established a funeral service, in which he prepared the corpse, hired the wailers and did the whole send-off.

St. Patrick’s Church on Bridge Avenue was founded in 1853, and in 1865 St. Malachi’s Church was founded to serve the poorest Irish families, who were living in the area overlooking the docks, known as the Angle. The Angle was north of Detroit, east of W. 28th St. and down Washington Avenue to Whiskey Island.

|

| 1994, The Hungry Five pluse one. Front, from left, Ruth, Leona, and Curly. Rear, Eileen, Jim, and cousin Janet Bolger. |

|

| Martha (Sabol) Wright took this photo on Achill in 1988. Slideshow has photos of Jim and Christine Breiner's 2003 visit. |

Ruth Breiner’s visit to Achill, September 1981

Ruth and her daughter Mary spent more than a week driving around the west of Ireland. Ruth wrote in her journal: “I was so glad not to miss Achill. It was a detour off the main road but it was worth the whole trip. Biggest island in Ireland, about 10 miles wide. We took the ‘famous Atlantic road’ (never heard of it) and it boggled eyes and mind. Gorgeous. Stood at the top looking out over the Atlantic with the wind blowing. Turn around and there are rounded mountains left and right, green hills and you see way off in the distance green expanse, houses, lakes, etc. You need a camera going around in a full circle to get it all in. Anything after this is anti-climactic, I think. Westport [an hour from Achill] is the prettiest city we’ve been in so far. You drive down a steep hill and it’s sort of nestled down at the bottom there, a river running though the middle so there are two bridges over.”

More from the Irish side

The Lavelles had some interesting personalities in the family. Nan Lavelle’s brother Tommy was a Cleveland firefighter for 44 years, and one of her sisters, Ella, married another Cleveland fireman, Patsy English. Their son, Jack, graduated from West High and was given a full scholarship to John Carroll University. He was editor of the Carroll News. After graduation in the late 1930s, Jack English went to New York City and became involved with the Catholic Worker newspaper. He was working for the legendary Dorothy Day, the founder and leader of the Catholic Worker Movement. He joined the Air Corps, became a bombardier, was shot down in the Ploesti Oil Raid over Rumania, and was taken prisoner. He was beaten badly by his German captors. After the war he ended up as a Trappist monk at the same abbey in Kentucky as Thomas Merton. Ruth thought this was very ironic, since Jack was a chatterbox by nature and the Trappists take a vow of silence. “I remember that my mother and her sisters all flew down [to Kentucky] for his ordination. It was there that my mother met Dorothy Day, who also had come. Jack later was at the abbey in Georgia.” He died of a heart attack in 1972.

Teresa Lavelle married Al Bolger, and their daughter, Janet, continued a family tradition of religious dedication and became a nun. Nan’s aunt Nitty (Anna Loretta Gallagher) and her husband, Patrick, had a son, Joseph, who became a Jesuit and was an assistant pastor at Gesu parish.

A final word from Ruth

“I want to say one thing. I’ve been reading ‘The Holy Longing,’ by Ronald Rolheiser only because we’re doing it in the study club that Jean Williams got me into many years ago. I’m not sure if I really like this book. It’s tough to read, but this I love: ‘One of the great anthropological imperatives, innate in human nature, is that we eventually must make peace with the family. No matter how bad your mother and father may have been, some day you have to stand by their graveside and recognize what they gave you, forgive what they did to you and receive the spirit that is in your life because of them.’ Not that I have anything to forgive my parents for. I know they loved us.”

Note to the Third Generation from Jim Breiner (2003)

If this is complicated, it is because families are complicated. If you go back on your own family tree for five generations, you have two parents, four grandparents, eight great-grandparents, 16 great-great grandparents and 32 great-great-great grandparents. If each of them has four or five siblings and their spouses and kids, you can see how it gets complicated very quickly.

This little narrative is just the beginning of the story. Take some time to talk with your parents about their lives, which are filled with great drama, humor and tragedy. Capture their words on tape and in writing, and collect the pictures before you forget who is in them. These memories are not with us forever. If Elsie had not taken the time to write down her recollections, we would have missed out completely on a fascinating chapter in the history of Germany, the United States and our family.

Sources (from 2003)

Interview with Leona Hausser, 2002. Letters of and interviews with Ruth Hausser Breiner, 2002-03. Interviews with Jim, Eileen and Curly Hausser, 2003.

U.S. Census records, available in the National Archives and online through Ancestry.com, have tremendous amounts of data about each individual in a family, including age, occupation, marital status, literacy, native language, country of origin, year of immigration, home ownership and so forth. These records also show who was living in the neighborhood, another rich source of research.

Mary Breiner took photographs of the Lavelle homes in Cleveland.

The Library of Congress has a 65-volume set of "Germans to America: Lists of Passengers Arriving at U.S. Ports," Ira R. Glazier and P. William Filby, eds. This has records of the Gilles family’s immigration (nothing on the Haussers).

Elsie Hausser’s typewritten narrative of 1981 has a great deal of detail about the Gilleses and Haussers that would otherwise be lost to us.

Some of the Gilles research comes from a Gilles database created by David L. Gilles, 4043 Circle Haven Road, Anaheim, Calif., 92807 714.637.8497 nagx@aol.com Some of this information was assembled for David by Sally Bridget Catherine Arn, Sarngwtw@aol.com who lives on the East Side of town. Her grandfather was Christ Gilles.

Kevin Barry, son of Gertrude Lavelle Barry, also did extensive research on the Gallaghers and Lavelles. kev_flo@qwestonline.com

No comments:

Post a Comment